By HVN’s Chief Scientist, Professor Richard Mithen

The plants of Aotearoa New Zealand (in common with plants throughout the world) have two names: a common or cultural name, and a scientific or systematic name (‘one flora; two systems’). For example, kawakawa is also known as Piper excelsum G.Forst.; horopito as Pseudowintera colorata (Raoul) Dandy; kauri as Agathis australis (D.Don) Loudon; and titoki as Alectryon excelsus Gaertn.[1]

The systematic name has usually been proposed by botanists of European descent, and rarely reflects the cultural name of the plant species given to it by indigenous peoples.

Two Auckland academic scientists, Professor Len Gilman of AUT and Dr Shane Wright of University of Auckland, have proposed that the scientific names are retrospectively revised to include the indigenous common names. In effect, to ‘decolonise’ the systematic names in a similar manner to the re-instatement of indigenous names for localities and geographic features.[2]

It is suggested that such changes would “herald an important step in the affirmation of Indigenous People’s contribution to nomenclature and knowledge”.[2] It would not be an easy process – plant systematic nomenclature is governed by an internationally agreed nomenclature code, and the changes proposed would be contrary to its principles of priority and publication.

For example, in the proposed renaming, Agathis australis would become Agathis kauri and, I guess, Piper excelsum would become Piper kawakawa. The use of the Māori names for the species epithet is not without precedent. The botanist Allan Cunningham used the Māori names as part of his systematic name for several New Zealand plants in the 1830s, such as Eugenia maira A.Cunn., Persoonia toru A.Cunn., Laurus taraire A.Cunn., and Laurus tawa A.Cunn.[3] While later taxonomists have changed the genera to which these trees belong, the specific epithet of the Māori name remains, in accordance with the principle of priority and publication.[4]

While there may be merit in this proposal, there would be some losses. Both cultural and systematic names have whakapapa, as those of kawakawa and Piper excelsum illustrate.

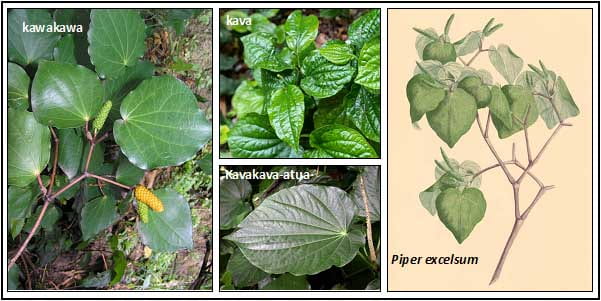

Following their arrival in Aotearoa, the ancestors of Māori would have been the first people to encounter the plant that we know as kawakawa. No doubt they would have recognised the plant’s similarities to two other species that are found in Polynesia – Piper methysticum, commonly known as kava, and Piper latifolium known as kavakava-atua in the Cook Islands (Figure 1) – and named this new plant accordingly, reflecting its similarities to these other plants, including its bitter taste.

Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander would have been amongst the first non-Māori to encounter kawakawa, expertly painted by Sydney Parkinson, as part of the botanical collecting during James Cook’s first expedition to New Zealand in 1770 (Figure 1).

Following their return to London (Parkinson died of dysentery during the return voyage), Solander began to prepare a manuscript Primitiae Florae Novae Zelandiae which, along with the illustrations of Parkinson, would have become the first systematic flora for New Zealand.

While Solander was familiar with the name kawakawa, he proposed the name Piper myristicum – ‘Piper’ as it was similar to other species, such as black pepper, that had been placed in the genus Piper by the Swedish botanist Linnaeus in his seminal work Species Plantarum of 1753; and ‘myristicum’ meaning fragrant, derived from the Greek noun myron meaning perfume.[5] However, Solander’s manuscript was never published, partly due to his sudden death in 1782 at the age of 49. As the rules of botanical nomenclature require all new systematic names of plants to be formally published, Solander’s name for kawakawa Piper myristicum has never been accepted.

Duplicates of the many herbarium specimens (but not kawakawa) collected by Banks and Solander are at Te Papa and can be viewed online.

In 1772 James Cook embarked on his second voyage to New Zealand, accompanied by the German scientist and naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster and his 18-year-old son Georg, who were employed to provide a science report of the expedition. In addition to collecting many zoological and botanical specimens, Georg Forster wrote extensively about the peoples of the Polynesian Islands, describing their social organisations, languages, customs and religions, and without the Western and Christian biases that are evident within the writings of many colonial explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries.

On his return, Georg Foster published an unofficial account of the expedition A Voyage Round the World to great critical and popular acclaim. It remains one of the most important accounts of the societies of the South Pacific Islands prior to significant European influence, and a seminal work in both ethnography and travel writing. It also helped him to secure a succession of academic positions.[6]

In 1786 Forster published an account of the plants he had collected from the South Pacific Florulae insularum australium prodromus. It includes the first published description of kawakawa, to which he gave the systematic name Piper excelsum, by which it is known today (Figure 2), along with the authority G.Forst.[7] The ‘type’ specimen of kawakawa collected by Forster in 1773 is within the Göttingen University herbarium and can be viewed online (Figure 2).[8]

In addition to his extensive botanical and ethnographical research and writings, Forster was a prominent figure in the European Age of Enlightenment. He became a leading figure in the short-lived Mainz republic of 1792–93 and was sent as a delegate to Paris to request that Mainz become part of the newly-formed French Republic. While he was in Paris, Prussian and Austrian troops regained control of Mainz, and Forster was declared an outlaw. He died penniless in exile in Paris at the age of 39, buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave.

The systematic naming of kawakawa by European botanists does not end with Forster. One of the benefits of accumulating large collections of plants, such as within the great herbaria of Kew and Paris, is that comparisons can be made from similar plants from different geographical locations.

The Dutch botanist Friedrich Anton Wilhelm Miquel published a review of Piper species in 1843 in which he decided that Piper excelsum along with the Polynesian species P. methysticum and P. latifolium were sufficiently different from other Piper species that they deserved their own genus, which he called Macropiper.

This subdivision is partially supported by recent DNA analyses, which unexpectedly also includes the African species P.capense into this small group of Polynesian Piper species.[9] Thus, kawakawa can now be referred to as either Piper excelsum (G.Forst.) or Macropiper excelsum (G.Forst.) Miq. Joseph Hooker’s Flora Novae-Zelandia, published in 1853, retains the name Piper excelsum. Whereas Thomas Cheeseman, the first director of the Auckland Museum, in his 1906 Manual of New Zealand Flora – the first comprehensive account of the New Zealand flora written and published in New Zealand – chose to use Macropiper.

Changing the systematic names of the plant species of Aotearoa New Zealand may help to affirm Māori contribution to plant nomenclature and knowledge, and may have merit.

It may also result in a loss of a part of history, maybe one that is often associated with colonisation and imperialism, but history, nonetheless. In the case of kawakawa, it may mean losing a link to the remarkable life of Georg Foster who, in addition to giving the somewhat uninspiring name of Piper excelsum to kawakawa, was an early exponent of the genre of travel writing and the science of ethnography and died at a young age as a revolutionary republican in France.

[2] Gilman and Wright (2020). Restoring indigenous names in taxonomy. Communication Biology 3: 609. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01344-y: Knapp et al. (2020) Indigenous species names in algae, fungi and plants: A comment on Gilman and Wright. Taxon 69(6) 1408–1413 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.12411: Wright and Gilman (2022). Replacing current nomenclature with pre-existing indigenous names in algae, fungi and plants Taxon 71 (1) 6–10 DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/tax.12599

[3] Annals of Natural History 1839 p 379; https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/22966#page/7/mode/1up

[4] Syszygium maire (A.Cunn) Sykes & Garn.-Jones; Totronia toru (A. Cunn.) L.A.S. Johnson & B.G. Briggs;. Beilschmiedia taraire (A.Cunn.) Kirk, Beilschmiedia tawa (A.Cunn.) Kirk.

[5] This noun is also the root of the systematic name of nutmeg, Myristica fragans, and the aromatic smell of both nutmeg and kawakawa is largely due to the same plant compound, known as myristicin.

[6] Forster taught at the Collegium Carolinum in Kasssel (1778-84) and at Vilnius University (1784-87). In 1788 he became Head Librarian at the University of Mainz.

[7] The specific epithet ‘excelsum’ refers to ‘height’ and may refer to the woody nature of kawakawa compared to many other Piper species.

[8] The naming of a plant species requires a single type specimen to which all other specimens may be compared, and the details of the type specimen are part of the description. Forster did not designate a ‘type’ specimen for kawakawa, but a ‘holotype’ has been subsequently designated from his New Zealand collection.

[9] Jaramillo et al. (2008). A Phylogeny of the Tropical Genus Piper using ITS and Chloroplast psbJ-PetA. Systematic Botany 33 (4) 647-660.